[ad_1]

The alpha male may be more of a myth than reality, as researchers have found that among many species, he is not the one in charge.

A recent study has revealed that female primates won far more power struggles than expected, and in most species, there is no clear male dominance at all.

Researchers from Germany studied real fights between 151 groups of male and female primates, who are among the most intelligent group of mammals, and include humans, monkeys, and apes.

They found that in the majority of cases, females pushed males aside, and even controlled the mating process, challenging the long-standing belief that male dominance is the norm.

Dr Elise Huchard, co-author of the study and evolutionary biologist at the University of Montpellier, told BBC Science: ‘If a female doesn’t want to mate, the male can’t do anything about it. That alone gives her power.’

For years, society has depicted the alpha male as the one in charge, leading the group, making decisions, and getting first pick of everything. That imagery has shown up in movies, on television, and even in school textbooks for decades.

However, it has left out a key fact: women are already proving they can lead, and not just in isolated cases.

In fact, the study authors said the idea that males are naturally dominant was based more on cultural bias than biology. Their research found female power is not rare or an accident, it is part of a broader evolutionary pattern seen across primate societies.

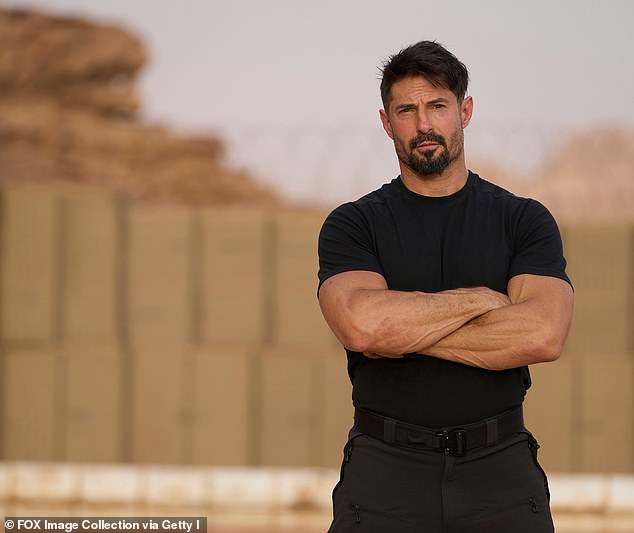

A study found that female primates often pushed males aside, and control the mating process

That is a big shift from the narrative of male dominance, especially considering that humans share much of their behavior with primates.

Researchers collected and analyzed years of detailed behavior records of primates, and tracked who initiated a conflict, who submitted, and who walked away as the winner.

The study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences looked at 151 primate groups and found that females came out on top in about one out of every eight cases.

Males were dominant in about one in every six cases, representing 25 groups from 16 different primate species.

However, in about 70 percent of these populations, power was more evenly shared, with both males and females able to win conflicts.

Scientists said the most surprising part was that strength alone did not decide who had the upper hand. In many species, female power came from control over mating.

In species where females chose when to mate and could not be forced by males, they used that choice as leverage.

Researchers said sex gave females a kind of bargaining power. If a male wanted to mate, he had to act right. If he got aggressive, she could turn him down.

In talapoin monkeys, the dominant sex shifted depending on the environment

The study found female dominance showed up more in species that lived in trees, where males and females are about the same size, and where mating tends to be monogamous.

Male dominance, on the other hand, was more common in species that live on the ground, where one male mates with several females, and where males are much larger.

In those cases, males often use their size to push females around and fight off other male rivals.

But even in species where males are usually in charge, scientists found exceptions.

In some groups of the same species, females took the lead. In talapoin monkeys, the dominant sex shifted depending on the environment.

Researchers also noticed something often overlooked, that about half of all observed fights were between males and females, not just within the same sex.

Dr Dieter Lukas, co-author of the study and researcher at the Max Planck Institute, said: ‘This kind of intersexual aggression, males, and females fighting each other, is common, and most studies have ignored it.’

In bonobo groups, females mate with several males, form alliances, and often lead the group

The team looked at five major theories to explain why females might end up dominant. The strongest support, they said, went to reproductive control and female competition ideas.

Reproductive control means females decide when and how to mate, like bonobo monkeys do, and that shifts the balance of power. In bonobo groups, females mate with several males, form alliances, and often lead the group.

Moreover, competition among females shows that female power can also come from fighting each other. In species like lemurs and meerkats, females compete over food, territory, or help to raise their young, and sometimes even dominate the males.

Some scientists had believed that strong female family ties or coalitions would lead to female dominance, but the data did not really support that. Even when females formed close social bonds, they did not always outrank the males.

Researchers said that how power plays out in a group depends on a lot of factors like environment, group size, mating system, and even individual personality. That flexibility could apply to humans too.

For instance, chimpanzees are mostly run by males. Bonobos are led by females. That suggests human ancestors might have followed more than one path when it comes to gender power.

A recent database by Leadership Circle showed that female leaders not only excel at building relationships, but the connections they create are marked by authenticity and a clear sense of how they serve a greater good beyond their immediate circle.

[ad_2]

This article was originally published by a www.dailymail.co.uk . Read the Original article here. .